In 2022, the global supply chain took hits on many fronts while still recovering from challenges presented the previous year. Transportation issues affected many areas of a specialty food business’ operations, including pricing, inventory, and relationships with retailers, foodservice operators, and more.

“Makers had widely varying experiences in 2022, but on average margins took a big hit as brands tried to maintain customer loyalty by not passing along every wave of price increases that flowed through the supply chain," explained David Lockwood, researcher behind SFA’s Today’s Specialty Food Consumer report.

Midyear supply chain issues included difficulties with supply and demand planning, product availability, and warehousing. Smaller food and beverage shippers most frequently cited store operations and transportation rates as primary challenges.

Makers also indicated that COVID’s impact on labor, over-the-road capacity constraints, port delays and congestion, and changes in consumer behavior all facilitated operation disruptions.

“Food and beverage shippers have contended with a lot lately, as the industry has been more affected by product and material shortages than most, and for goods that are in demand year-round,” said Glenn Koepke, FourKites general manager of network collaboration, in a statement. “Those who have navigated supply chain disruptions the most successfully are companies that have leaned heavily on technology and collaboration to identify and address issues before they snowball into major events.”

On the global front, the war in Ukraine had a negative impact on the global food supply chain because it strained the world’s fertilizer supply, Ukrainian exports like wheat, and sunflower seeds, as well as global fuel access.

Because of this, World Trade Organization director-general Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala told BBC that the war had the potential to elicit a global food crisis, without intervention.

“You can imagine what a big impact this is going to have, even just on the African continent,” Okonio-Iweala said. “I hope that we don’t go into a really severe food crisis for the next couple of years.”

Ukraine contributes to 9 percent of the global wheat market, as well as 42 percent of the global sunflower oil market, and 16 percent of the global maize market, all of which were deeply affected by Russian blockades and other war-related externalities.

This worry compelled the two countries to sign two export agreements: one guaranteed the safe passage of commercial ships from three Ukrainian ports, and the other facilitated Russian grain and fertilizer exports.

In October, Ukraine's exports of agricultural products nearly returned to prewar levels, easing pressure on global food prices.

Later that month, a lack of rain in the Ohio River Valley and Upper Mississippi caused sections of the Mississippi River to approach 30-year water level lows. In addition to shipping issues that prevent boats from using portions of the river, the drying areas were also vital for agriculture, oil, and building materials.

Restricted access caused shipping costs to skyrocket. For example, the cost of sending a ton of corn, soybeans, or other grains from St. Louis to southern Louisiana jumped from $49.88 on September 27 to $105.85 on October 11, according to The Wall Street Journal.

In November, President Joe Biden called on Congress to block a rail strike after a rejection of a five-year contract related to workers’ benefits and compensation by rail workers.

“It’s not an easy call, but I think we have to do it. The economy is at risk,” President Biden said. Fears of a holiday catastrophe underpinned the conversations, with many products relying on the rail system to transport goods across the country.

The Senate passed a bill that forced unions to accept a tentative agreement that makes a strike illegal. But this ruling did not find complete bipartisan support. For example, Senator Bernie Sanders rejected the bill after the motion to offer paid sick leave was denied.

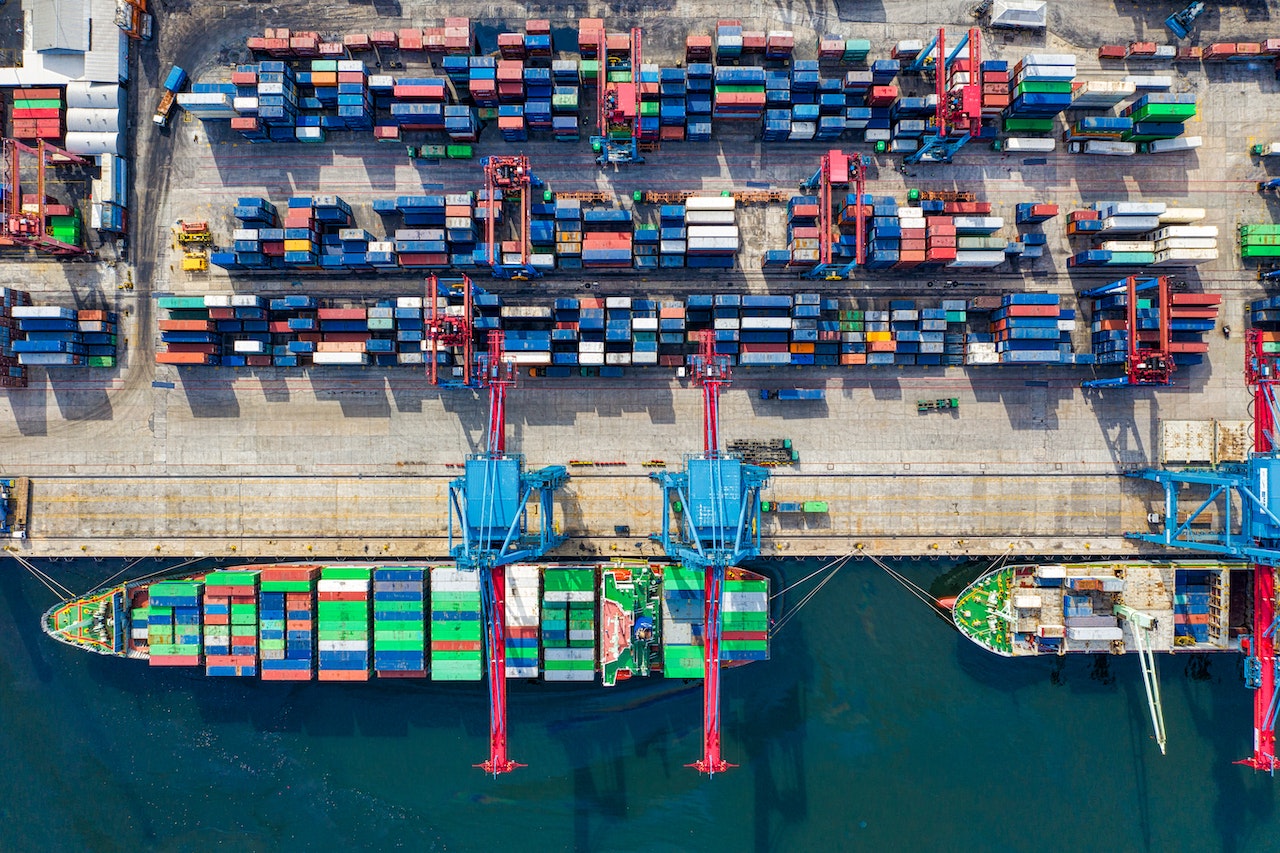

Throughout the year, supply chain bottlenecks improved at ports in California after the issue plateaued in January, 2022, with 109 backed-up ships.

“Our workforce is now managing reasonable levels, and the stress level is down,” said Captain J. Kipling Louttit, a former Coast Guard officer who’s the executive director of the Marine Exchange of Southern California & Vessel Traffic Service Los Angeles and Long Beach. “We’re back to being in a good place.”

Oxford Economics’ U.S. indicator of supply strains also agreed with the improvement. “Supply chain conditions should stay on a more encouraging trajectory in the final stretch of 2022 and in 2023,” said Oren Klachkin, the company’s lead U.S. economist.

Looking ahead to 2023, forecasts by Capterra, a software firm researching small and medium-sized businesses, found that these businesses are investing in software-based emerging technologies for their supply chain at twice the rate of hardware-based tech. It also found that seasonal forecasting has helped to reduce excess inventory concerns, and the top supply chain stressors going into 2023 are the strained economy and low inventory.

Despite many factors contributing to a difficult year for the supply chain, industry experts are largely optimistic that the situation will continue to improve in 2023.

Related: USDA Invests in Bioproduct Manufacturing; Small Businesses Optimize Supply Chains in 2023